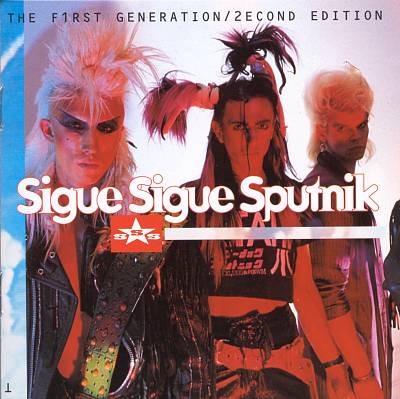

Sigue Sigue Sputnik

Robert Rankin sparked a discussion of Sigue Sigue Sputnik on Facebook last week:

I am trying to remember the name of this really dreadful UK band in the nineteen eighties, they had a couple of minor hits with a sort of techno sound, the lead singer wore a fishnet stocking mask (they looked a bit like Slipknot looked later) and I recall Janet Street Porter was a big fan for some reason. I know they got booed of the stage because they played to tapes. I think there were two words in the band’s name and for some reason there was a Russian connection somewhere. Does any of this ring any bells?

The Sigue Sigue Sputnik story is a bit more interesting than that. Tony James has written about it at length, but I thought a briefer summary might be worthwhile. You could call this a defense of a misunderstood band, if you like.

First of all, it’s important to understand context. Just as you can’t understand the importance of The Beatles if you assess them as if they were a modern band, so you can’t understand Sigue Sigue Sputnik unless you recall early 80s England. Yes, I just mentioned Sigue Sigue Sputnik and The Beatles in the same sentence; I think I hear Alexis Petridis having an aneurysm. But recall that The Beatles were initially dismissed by many as a dreadful boy band. Record company Decca memorably wrote that “The Beatles have no future in show business”, because “guitar groups are on the way out”. The Monkees, too, were mocked mercilessly, even after they managed to wrest artistic control from their corporate manufacturers.

The Monkees were still being mocked in the 1990s as vapid and unable to play their instruments; but in the early-to-mid 80s, it was synth bands who were the pariahs of UK music criticism, including another band dismissed as a manufactured boy band pop act, Depeche Mode. The music press had a major hate-on for anything involving synths; even Paul Morley, who would later go on to write about the joys of electronic music for ZTT, was required to gently mock Depeche Mode when he wrote for NME:

So I’m surrounded by three of the sweet Depeche boys, impressed by the variety of their haircuts, surprised by their simplicity […] There is a residue of scurrilous schoolboy values, an innocently mutinous streak. They’re in no hurry: they’ve a cheerily vague idea about where they’ve been, and aren’t too concerned about where they’re going. […] Soothing and exciting, pop’s equivalent to the TV commercial.

Attitudes towards synth bands didn’t really start to change until 1986, when a music journalist achieved commercial success as figurehead of a synth band. Once Neil Tennant and Pet Shop Boys hit the UK charts, it gradually became unacceptable to automatically rubbish all synth music as a matter of principle. But that change was still a few years in the future for Sigue Sigue Sputnik at the time of their first single, so it was inevitable that the UK music press would hate them. And if you want to carry on hating Sigue Sigue Sputnik, stop reading now, because I’m about to reveal the secret.

Sigue Sigue Sputnik was both fantasy and satire, an exercise in tongue-in-cheek mockery and deliberate hype. The rumors of being signed to EMI for the then-outrageous sum of £4m? Untrue, as Muriel Gray hinted at in an interview. Selling ad space between the tracks on their album? Another satirical jab at commercial pop; some fake sampled and cut up ads on the album provided verisimilitude. The rumors that the band couldn’t play their instruments and were just miming to tape? Untrue of Sputnik, though true of many other bands. In short, Sputnik set out to inspire outrage; Tony James had even considered naming the band “Sperm Festival” or “Nazi Occult Bureau”, before deciding that was a little bit too unsubtle. When a Radio 1 DJ described the band as “truly appalling”, they printed it on the sleeve of their next 12″ single.

The band’s music was an interesting merger of rock’n’roll guitars with the (then brand new) tool of sampling, backed by a Giorgio Moroder inspired synth bassline. (Moroder produced “Love Missile F1-11”, though he was bemused by the band’s determination to keep the bassline as unornamented and relentless as possible.) Whether the music is to your taste or not, it has the virtue of being original and interesting, and not just another sneering indie guitar band of the kind the music press loved. It also set out to confront; slathered on top of the songs were hundreds of samples, carefully chosen to be provocative. Sadly, many of the best ones were removed at EMI’s lawyers’ request, and didn’t get heard until the band released some of the original mixes decades later; however, prominent in “Love Missile F1-11” was a sample from “A Clockwork Orange”, which at the time was still banned in the UK. Sputnik sent out press photos of a mock-crucified band member on a cross made of TV sets, with Tony James grinning and mugging at the camera. Pretty much the perfect setup to make the Daily Mail incandescent with outrage, and it worked. The other tabloids, too, gleefully printed every rumor they were sent, and Sigue Sigue Sputnik were suddenly famous — even if it was infamy. A hit single followed.

Back in the 80s, it was popularly believed that “There’s no such thing as bad publicity”. Of course, now we know better, having seen Amy Winehouse smoking crack and crawling around paralytically on the floor licking ashtrays, but back then people really believed it. However, it wasn’t long before Tony James started to see the downside of inciting media outrage. As Lemon Kittens memorably put it, those who bite the hand that feeds them sooner or later must meet the big dentist. Rumors caused friction in the band, and led many to dismiss the music as a joke.

Another problem was that by the time of Sputnik’s second album, it was necessary to find new seams of hype, loathing and outrage to mine. The UK charts had been infested with endless hit singles produced by “The Hit Factory”, also known as Stock, Aitken and Waterman. Sputnik opted to get SAW to record and mix a (deliberately) horrible Sputnik, Aitken and Waterman track called “Success”, with lyrics boasting about the delights of being a manufactured pop band. It failed to hit the top 10, but SAW’s formulaic songs also never made the US top 10 again, so it wasn’t all bad. (That Donna Summer track doesn’t count because she co-produced it.)

But that was it, as far as Sputnik’s commercial success went. A brief stop at number 50 in the charts for “Dancerama”, and then a long silence. It wasn’t until the real 21st Century that the 21st Century Boy ideas of Sigue Sigue Sputnik started to get reassessed. Sputnik came back, quietly, via the Internet; this time the music was the main event. I picked up the self-released CD “The Ultimate 12″ Collection”, and learned what the singles had been supposed to sound like — a revelation in some cases. The new Sputnik still appropriates the trashy sex and violence of movie culture through extensive sampling, but the hype is gone now, and (sadly) so is the fame.

But the spirit of 80s Sputnik lives on. Consider Die Antwoord, the South African band with a secret art school background who engage in some epic media trolling. Check out their video for “Fatty Boom Boom”, which features a Lady Gaga lookalike touring South Africa, getting carjacked, and having a backstreet abortion. The whole thing is so carefully, calculatedly, artfully offensive that it almost wraps around and passes through the other side into acceptability. The Daily Mail, of course, were delighted to give it publicity. Some things never change.